Is AI already as good as a junior lawyer?

An experiment with NotebookLM shows what AI can — and can’t — do with 1,700 pages of legislation.

Many legal and HR professionals are wondering when — not if — AI will start meaningfully reducing research grunt work. This article documents a simple experiment to test that idea: could a freely available AI tool handle a task we’d normally give to a junior lawyer?

The freely-available AI tool is Google’s free NotebookLM tool, an AI-powered research assistant that allows you to upload your own source material (think legislation, case law, articles, or internal memos) and uses only that material as the source for answers to questions. [Note that I have no affiliation with Google - it’s just a free tool I used for this analysis.]

Unlike ChatGPT or other LLM AIs (which draw on a vast but generic knowledge base), NotebookLM lets you curate the source material. This reduces (potentially eliminates) AI ‘hallucinations’ and gives assurance that the AI is not going off on a frolic into unverified sources in its quest to be helpful. In theory this positions tools like NotebookLM well for the legal profession, where accuracy always trumps speed and convenience.

I have been more than impressed by NotebookLM’s performance at the tasks I have set it, and the standard of its responses begs the questions:

Is NotebookLM at or near the level of a junior lawyer?

What are the limits of trusting it?

How can it be used right now?

How could these tools shape the future of legal practice or professional work?

1. The experiment: AI v Fair Work Act

The baseline test

I uploaded the official version of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) to a notebook in NotebookLM (I won’t detail here how to sign up for NotebookLM.)

NotebookLM ‘read’ all ~1,700 pages of the FW Act in around 30 seconds (impressive in and of itself), after which it was primed to start answering questions about Australia’s employment law framework.

I first gave NotebookLM this prompt: “Provide me with a brief summary of what an employer needs to take into account before terminating someone’s employment.”

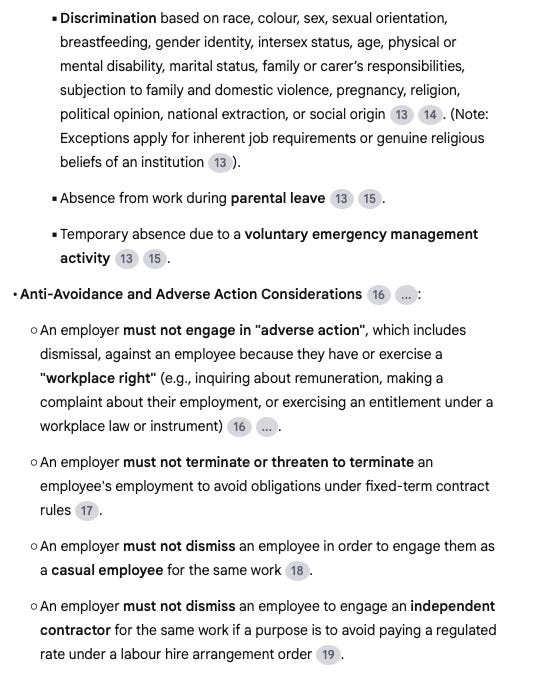

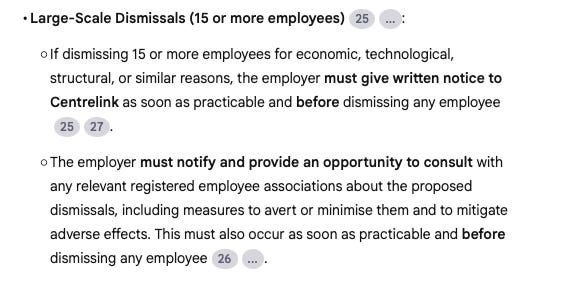

NotebookLM’s full 1,500-word response is copied in full at the end of this article as a series of screenshots. In summary, in less than 15 seconds NotebookLM generated an incredibly comprehensive summary of FW Act provisions that govern termination of employment, including: notice of termination, pay in lieu of notice, unfair dismissal considerations, genuine redundancy considerations, general protections considerations, and notification requirements for large-scale dismissals involving 15 or more employees.

As a baseline answer to my question, the standard was very, very good. If I was tackling the question from scratch, I think this might have taken me 1-2 hours to both identify all of these provisions and then accurately summarise them with references.

NotebookLM also surfaced aspects I might have overlooked — like Centrelink notifications or union consultation requirements — had I assumed the question only applied to a single termination.

But NotebookLM’s answer wasn’t perfect.

First, NotebookLM repeated itself in a number of areas in its answer. Not a fatal flaw in the output, but these drafting defects undermine confidence and present a free-kick to naysayers who delight in pointing out AI shortcomings.

Also, a useful part of NotebookLM’s functionality is that it inserts footnotes in its answers that link directly to the specific section of the source material it has used to answer the question. This enables efficient human verification of answers. But some of the footnotes in NotebookLM’s answer in my test appeared to link to incorrect sections of Act. Again, an unexplainable drafting defect and another free-kick to naysayers.

Those are easily navigable quality issues that a human review could easily clean up if they were inclined to use NotebookLM’s output in an email or advice. The real problem was not what was included in NotebookLM’s answer, but what was not included in the answer.

NotebookLM missed something that really should have been included, which is when payment in lieu of notice must be made.

When I asked NotebookLM specifically about this, it wasn’t able to decipher the FW Act to uncover the position arrived at by the Federal Court in Jewell v Magnium Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2025] FedCFamC2G 676, i.e. that pay in lieu and paying out annual leave must occur before the employment is terminated.

I first asked NotebookLM this: “Are there any timing requirements that govern when an employer must provide termination payments?”

Its response was that while the FW Act creates obligations to make a number of payments on termination of employment, there is no concrete number of days within which the payments should be made. Technically this is accurate - but it is not quite correct.

I then asked NotebookLM whether section 117(2)(b) of the FW Act had the effect of governing the timing of certain termination payments. NotebookLM reconsidered its position and conceded the point, saying now that it agreed section 117(2)(b) acts as “a prerequisite for lawful termination by an employer.”

Again, this is technically accurate, but to me is also not quite right at the same time: failing to meet the requirements of s.117(2)(b) isn’t a factor in whether a termination is ‘lawful’, as that expression has a specific meaning in employment law.

The more accurate response would have been to acknowledge that s.117(2)(b) requires pay in lieu of notice to be made prior to terminating the employment, and failing to do that is a breach of the National Employment Standards, possibly attracting monetary penalties for the employer.

Going all-in on an employment law superbible

I quickly went beyond the FW Act and added more sources to my Notebook. I uploaded a range of other verified documents: the Fair Work Regulations, the Fair Work Rules, the Explanatory Memorandum to the original Fair Work Bill, the Fair Work Commission’s case law benchbooks, a range of Modern Awards, Work Health Safety legislation, Long Service Leave Acts, and a compilation of Fair Work Commission bulletins from the last few years.

(As an aside, for HR practitioners this could serve as the ‘Guide to the Fair Work Act’ you have been looking for, conveniently in situ on your iPhone and ready to instantly give you a pretty thorough answer to any of the varied employment questions that hit your inbox every day.)

My employment law superbible was a veritable treasure trove of source materials that I could now have NotebookLM use to answer questions like:

When do I need to consult with my employees?

In what circumstances are union officials allowed to enter a workplace?

What is a valid reason for termination of employment?

What steps do I need to take to make an enterprise agreement?

Again: the answers were immediate, overwhelmingly thorough, and it would took some working knowledge of the FW Act to spot where answers were slightly off or missing key information. But these were staggeringly fast, well-written first drafts of answers.

(As an aside, I have found that the people who have been most impressed by this output are other lawyers. I think knowing how much goes into writing a succinct summary of legislative provisions amplifies the wonder at how quickly AI can perform these tasks.)

What I also found was that NotebookLM’s answers became seemingly less useful as I added more and more source material. NotebookLM appeared to take a ‘more is more’ approach, piling in everything it could identify as relevant to the question.

This may have more to do with my prompts than anything else, but if NotebookLM — a highly sophisticated AI — struggled with the FW Act, that isn’t just a comment on the tech. It’s a comment on the system. If a 1,700-page legislative instrument, riddled with dependencies, cross-references, and interpretive nuance, confuses an AI trained on trillions of tokens... perhaps the problem isn't the AI?

2. NotebookLM’s performance and what it tells us

NotebookLM’s output is genuinely amazing. To see an incomprehensible amount of source material synthesised in real time in a matter of seconds is astounding. I can understand why the ‘AI will take our jobs’ narrative exists.

But the combination of drafting defects and oversight of important compliance requirements means NotebookLM isn’t ready to do a junior lawyer’s job just yet. Its output would not be acceptable in its raw form, not to a law firm or a business.

I think what NotebookLM is, though, is a tool that can add incredible value to legal roles right now. Rather than replacing junior lawyers, it could be the tool of choice for the types of work junior lawyers are asked to do. In fact, it might be that clients begin demanding use of this tool (or tools like it) to reduce legal spend on ‘reading in’ or other types of groundwork.

It raises complex questions for law firms in particular, especially those still wedded to the billable hour. If AI tools like this can significantly reduce the time taken to provide advice, these tools also significantly reduce client fees. This presents a commercial impediment to embracing this technology.

But one of the biggest strategic advantages law firms and legal teams have is proprietary curation. The power of NotebookLM (and tools like it) scales directly with the quality and currency of its source materials. Firms that can maintain well-structured, up-to-date libraries of relevant legislation, case law, commentary, and internal precedent (accompanied by a well-engineered and well-tested prompt guide) can offer clients a living, breathing knowledge base — one that’s consultable by humans and machines alike. In this model, the value isn’t just legal advice — it’s the architecture of legal knowledge. And producing and maintaining this knowledge base is not something you charge a one-off fee for like you would do currently for a piece of advice - with this you are creating something you can charge for over and over again.

I think this is especially valuable for clients operating in niche legal areas where there isn’t enough size for the big legal publishers like LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters to provide a subscription service. This is where firms could curate a bespoke knowledge base of regulation, precedent and internal company documents - all guaranteed to be up-to-date and with outputs ready for human verification at a set fee.

AI tools like NotebookLM probably won’t replace the work of junior lawyers, but they will likely change the work junior lawyers do.

And law firms overall are probably safe, too. My test results are a perfect example of why even the best AI still needs human oversight in this space: not because it fails, but because law isn’t just what’s written, it’s what’s been interpreted.

3. Ideas for future use cases

I think with AI that the sky is no longer the limit. There are so many potential applications for it that go beyond the tech bro hype of 10X productivity and making $30k before lunch using vibe coding.

For NotebookLM and closed-language AI tools like it, I can see immediate application in Australian workplaces. I work in employment relations and so my ideas focus on that area of work, but here is where I see this tool (or a tool like it) adding great value:

Dismissal assessment tool

You’ll often hear organisations search for a consistent standard to apply to decisions about whether to end someone’s employment. Leaders will ask: what have we done before in these circumstances? When have we thought it appropriate to issue a written warning rather than dismissing someone?

How about loading up a Notebook with all of your historical Form F3 unfair dismissal responses and use that as an AI-powered dismissal assessor? All of your previous dismissal decisions would be compiled into one repository, readily searchable for all of the scenarios where you have previously considered you have a valid reason exists to dismiss someone. It turns your HR history into a judgment calibration tool — consistent, scalable, and defensible. It retains organisational memory beyond the people who are currently doing the work.

Add into your Notebook the Fair Work Commission’s case law benchbook on unfair dismissals, and scrape the FWC decisions database (ethically, of course) for 2-3 years’ worth of unfair dismissal decisions. Now you have an incredibly robust dismissal assessment tool at your disposal, and you’re no longer relying on how your decision makers have calibrated their personal moral compass on workplace misconduct or performance.

Always-ready employee handbook

Load all of your HR policies, procedures and enterprise agreements into a Notebook and have it serve as your employee handbook. No need to revisit summaries every time you update a policy - just put your new document in the Notebook and you’re done.

This would put your employee handbook in every employee’s hand at all times, whether they’re in front a company laptop or not. And it’s always current.

FWC analysis tool

Create a database of FWC decisions on a particular issue (using ethical website scraping, of course) in a Notebook and use it to identify hidden patterns or trends that you otherwise wouldn’t see.

For example, I loaded >500 decisions from the FWC about protected action ballot orders and had it summarise trends like most utilised forms of protected action, agreed safety carve-outs and circumstances where the FWC had required an extended notice period for PIA. This would have taken a human weeks of work.

While my focus is employment law, the use cases here are clearly transferable. A litigator could use this to ingest pleadings and discovery materials across multiple jurisdictions. An in-house commercial team could load contract templates, risk matrices, and playbooks into a notebook to serve as a frontline negotiation co-pilot. A regulatory affairs team could build notebooks for each compliance domain (environmental, anti-bribery, privacy) and use AI to pressure test decisions before escalation. This is a horizontal capability, not a vertical gimmick. Any domain where text-heavy complexity meets repeatable reasoning is a candidate.

And of course, NotebookLM can reduce workload but it doesn’t replace responsibility. Anthropic frames AI reliability in terms of the "4 D’s": determine, detect, double-check, and document. Even when AI tools are powerful, they still require human verification to detect gaps, double-check critical outputs, and document the reasoning chain. In legal practice, this isn’t optional. It’s professional duty.

4. What do AI processes tell us about the current state of the law?

We often talk about access to justice and legal simplicity. Tools like NotebookLM might inadvertently become a diagnostic tool for legislative reform, surfacing complexity not even experienced practitioners notice because we’ve all become too good at tolerating it.

And what would legislation look like if it was redesigned for AI agent use? Can you imagine Acts written in modular structure with embedded machine-readable metadata? Perhaps, but how do we balance ease-of-use with the human condition: the ambiguity that frustrates AI is often what allows legal systems to handle edge cases and evolving social norms. Concepts of reasonableness and use of ‘best endeavours’ pervade legal work because human issues require human judgement. Making law more AI-friendly might make it less human-adaptable.

Maybe the more pressing challenge is how to convince our peers and mentors to dip a toe in the water. AI advancements are not measured only by processing speeds and tokens; they will also be measured in real-world use cases designed by people outside the tech sphere. We’re at the point now where the bottleneck is no longer just legal knowledge — it’s legal systems, legal tools, and legal mindsets. The firms and functions that master AI fluency, curated knowledge architecture, and defensible human-machine workflows will be the ones that thrive in this new era. This article isn’t a conclusion. It’s a signal: the work is just beginning.

Great article Ben!